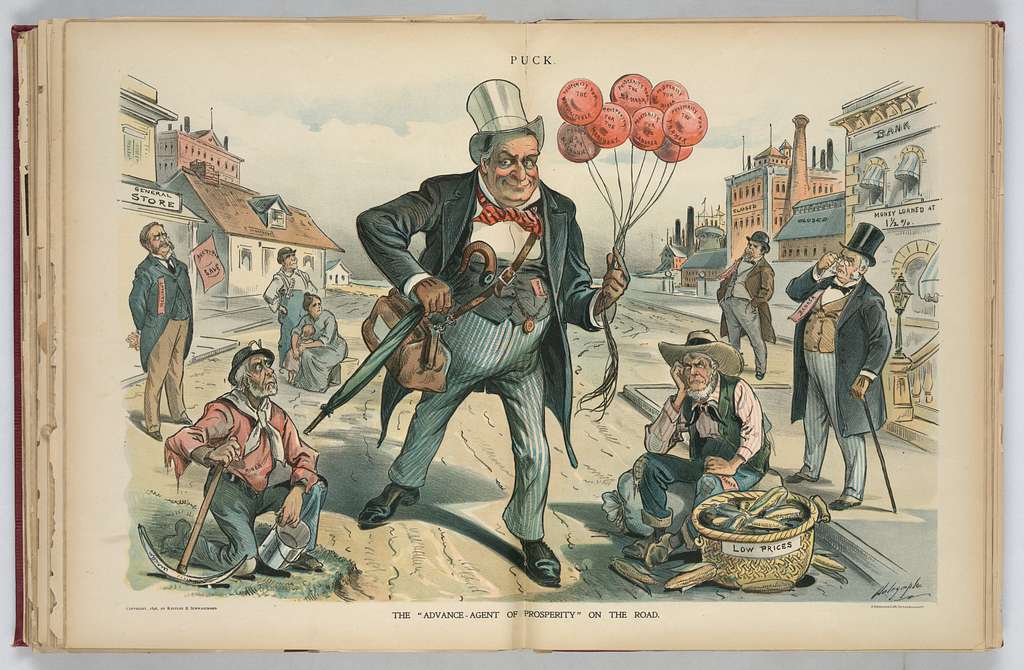

The United States’ ever-increasing political tension and the fact that the top 1% of Americans hold 30% of the nation’s net worth begs the important question: Is America in another Gilded Age? Let’s peel back the curtains on how the current socio-economic conditions may constitute the United States’ Second Gilded Age.

Before we go any further, what was the First Gilded Age? This term refers to the period between 1877 and the early 1900s, after the era of Reconstruction and in the midst of American imperialism in the Pacific and Caribbean regions. The term “Gilded Age” was coined by Mark Twain; gilded describes how the outside of the nation was covered in gold, while the internal core was a much cheaper metal, like copper or iron. In other words, gilded implies a mirage of success, covering up a politically tense, calamitous inner reality. This term perfectly describes the late 1800s; Andrew Carnegie and John Rockefeller, steel and oil tycoons, respectively, portrayed an illusion of success to foreign individuals. Analysis suggests that at one point, Carnegie’s wealth totaled 2.1% of the entire United States’ Gross Domestic Product (GDP) – a value well over $300 billion after accounting for inflation.2

While Carnegie and Rockefeller, among other wealthy industrial moguls, were enriching themselves, their enterprises abused working-class Americans, subjecting them to low pay, long hours, and brutal working conditions. For example, in 1911, workers at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in New York City were locked into the main quarters by their supervisor to prevent the women workers from taking extended breaks. When a fire broke out in the building, these women were unable to escape and were left to either jump out of windows to their deaths or inhale the dark smoke until they suffocated.

Outside of the economic turmoil of late 19th-century America, the United States endured substantial political and social battles as well. Immigration into the nation was substantially reduced or completely prohibited, particularly via the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which banned all immigration into the United States by Chinese laborers for 10 years. At the same time, Black Americans faced further challenges to their rights with the rise of the Lost Cause and Jim Crow movements in the South. While these examples only scratch the surface of the societal turmoil of the First Gilded Age, the challenges to the civil rights of millions of Americans on the basis of race and nationality demonstrate the exclusionary reality of American life during this period.

Essentially, the Gilded Age was filled with prosperity for wealthy, white Americans, but was an utter disaster for industrial workers, immigrants, and Black Americans–realities which parallel the state of American society in the 2020s.

To begin this comparison, let’s examine the connection between the prosperity of America’s social classes. While the list of ultra-wealthy Americans has diversified since the late 1800s, with Americans from a diverse array of backgrounds, such as Asian-American Jensen Huang, the CEO of NVIDIA, possessing fortunes in the hundreds of billions, these ultra-wealthy individuals nevertheless retain a similar grip on the American GDP as their early 20th century counterparts.3 Analysis by Visual Capitalist suggests that the United States’ top 0.1%–individuals who have a net worth greater than $25 million–collectively possess 13.8% of the United States’ current GDP, a figure in the realm of $3.64 trillion.4 Although Carnegie alone controlled 2.1% of the GDP, the fact that roughly 14% of the American economy’s value is held by the ultra-wealthy is a clear parallel to the First Gilded Age. Meanwhile, according to the 2023 Census, the average per capita income was $43,289, and the percentage of Americans in poverty was 11.1% (roughly 38 million Americans).5 The US poverty line for a single person is defined as a yearly income below $15,650, while for a family of four, the poverty line is $32,150.6 This situation is eerily similar to the unjust economic reality for the millions of working-class Americans in the late 19th century, and is arguably the most significant proof for the existence of an ongoing Second Gilded Age.

The second and third aspects of this comparison are heightened political and social tensions. During the First Gilded Age, tensions over immigration and racial divides plagued the political and social spheres of American society. In the 2020s, similar struggles over these issues consumed political discourse. Immigration has been at the forefront of the past two presidential election campaigns; since Donald Trump’s inauguration this January, his administration has advanced anti-immigrant, pro-deportation rhetoric, even placing Secretary of Homeland Security Kristi Noem in advertisements broadcast on television, threatening deportation for migrant citizens. Recently, the illegal deportation of Kilmar Abrego Garcia, an American citizen, to the notoriously dangerous, gruesome CECOT prison facility in El Salvador has captured public attention. Despite the Supreme Court’s 9-0 ruling in Noem v. Garcia that the United States should “facilitate” the return of Garcia to the United States, the Trump administration has nevertheless taken no significant action to bring Garcia back to his country.7 Controversy over this deportation has even resulted in Senator Chris Van Hollen’s (D-MD) visit to the nation, during which El Salvadorian President Bukele staged fake drinks during the Senator’s meeting with Garcia to falsify Garcia’s true day-to-day reality in El Salvador and support the Trump administration’s pro-deportation rhetoric. While these harsh immigration restrictions are not placed on Chinese migrants as they were in the 1881 Chinese Immigration Act during the First Gilded Age, the recent limits on Latin American immigrants parallel that controversial piece of legislation.

With regard to heightened racial tensions, the 2020s thus far have been a pivotal period for the struggle for Black Americans’ civil rights. The Black Lives Matter protests following the death of George Floyd, at the hands of disgraced police officer Derek Chauvin, grasped the nation’s media coverage and public outrage. Floyd, who was arrested for using a counterfeit $20 bill at a local convenience store, would ultimately be arrested by Chauvin, who would kneel on his neck for such an extended period of time that Floyd suffocated and died.8 The subsequent outbreak of protests in response to this murder, calling for Chauvin’s prosecution and more awareness of Black Americans’ true reality in the face of racism, not only impacted the American political sphere but also extended to Europe, Oceania, and South America.9 Outside of racial tensions, clashes regarding Americans’ civil rights, particularly with regard to the SAVE Act and the struggle for suffrage in recent months, have heightened the already hyperpolarized political climate in the United States.10 While it is difficult to compare the long-lasting era of Jim Crow during the First Gilded Age with the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests, both situations have one clear connection: heightened racial divisions.

So, is America in a Second Gilded Age? The evidence is clear–an astronomical wealth gap, high tensions over immigration, and a continued struggle for civil rights are stark parallels to the issues that plagued late 19th-century America. Without a rapid change for the better, present-day America might continue to be what America was at the turn of the 19th century–wealthy on the outside, but gravely struggling on the inside.

Works Cited: